Company: Sun Insurance

Job role: Loss adjuster

There are pages on this website dedicated to former RSA colleagues, whether soldiers or civilians who lost their lives during both world wars. The list is sadly long. Their talents were lost to the world. While some sacrificed their lives, others such as Robert Cedric Sherriff survived the horrors of the trenches and went on to enjoy remarkable careers.

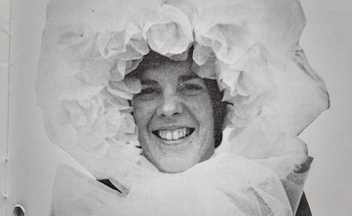

Robert “Bob” Cedric Sherriff was born in Hampton Wick, Middlesex in 1896. His parents were Herbert “Pip” Hankin Sherriff and Constance Winder. His mother would go onto have a significant influence upon his life. It was said, that wherever Robert went, Constance would follow.

The early years

Sherriff was educated Kingston Grammar School. He was quite the athlete and found delight in rowing, football, cricket and hockey. But, at the age of 14 he left school, and like his father before him, he became a (junior) insurance clerk at Sun Insurance Company. The year was 1912.

Sherriff’s middle class upbringing amid the green fields of Surrey could be described as the quintessential Edwardian dream. But those heavenly days were destined to be cut short for his generation when two years later, war broke out on the battlefields of Europe.

Outbreak of World War One

Like many youths his age, Sherriff was keen to be part of the ‘big show’. He joined the Artists Regiment, a volunteer unit formed in 1859 by architects, playwrights, actors, painters and musicians. As such, it was a natural fit for Sherriff.

At the outbreak of the First World War, the Artists Regiment was extensively used as an officer training school, at its base in Gidea Park in Essex. Other famous members of the Artists Regiment included Noel Coward, Wilfred Owen and the artist John Nash.

Sherriff gained his commission in the Artists Regiment, before being transferred to the 9th Surrey Battalion, the East Surrey Regiment, in France on 1 October 1916.

The impact of trench warfare

2nd Lieutenant Sherriff took part in several battles. In 1917 he was severely wounded at Passchendaele in the Ypres area of Belgium. Passchendaele was a series of battles renowned for the atrocious conditions of trench warfare in which they were fought. Sherriff received wounds to the face and neck when a shell hit a nearby pillbox sending fragments of concrete across the battlefield. Sherriff was lucky. His fellow officer, Second Lieutenant William Sadler, died in the same attack, possibly by the same shrapnel that wounded Sherriff.

He was hospitalised back in England, where he made a full recovery. It is possible that he first began working on the play that was to give him his big break, Journey’s End while hospitalised.

Journey’s End and post traumatic stress disorder

During his service in the trenches Sheriff admitted to suffering bouts of neuralgia (a pain that affects the nervous system). He wrote to his parents concerning this. Neuralgia had a bad press during the war. In some circles, it was viewed as a reason to be excused from active service or a loss of moral fibre, leading to assumptions of cowardice or being termed ‘shell shy’.

At the time, not enough was known about soldiers suffering from neuralgia and other possible forms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), yet it is worth remembering that the character, Hibbert, in Journey’s End, suffered from the same condition that afflicted Sherriff. Hibbert is suspected of cowardice by his senior officer and ordered to resume active duty. It is notable that Sherriff did not request to be sent away from the front line during his bouts of neuralgia. Despite his suffering, during his frontline service he was insistent on remaining in the trenches with his fellow soldiers.

Hibbert’s mental breakdown in Journey’s End is one of the most poignant moments of the play. And it most likely struck a chord with many who witnessed the production. It is possible, that similar to the film, All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), Journey’s End (1929) could be credited with starting conversations around PTSD that are still relevant today. Neither production sought to glorify war – but instead tried to understand its human impact and focused on the futility of war; a far cry from other jingoistic, sabre-rattling epics of the day.

A return to peace

Sherriff recovered from his wounds. After his hospitalisation his next posting was the Scottish Command to train others on the effect of gas warfare. Sherriff was promoted to captain before leaving the military in 1919 and returned to his previous employment at Sun Insurance where he worked as an adjuster. In his spare time though, Sherriff studied creative writing.

During this time Sherriff wrote and acted in several plays, using any profits to help fund local charities. In 1929 he staged Journey’s End. At this time WW1 plays were not received well by audiences. An already grieving nation certainly did not want to be reminded of the horrors of war.

Nevertheless, Journey’s End was a hit, and starred a 21 year-old fledgling actor named Laurence Olivier. It is a little known but poignant fact that Sherriff’s remarkable play was also produced in Berlin theatres, in post war Germany where it was re-titled The Other Side.

Sherriff embarks for Hollywood

RC Sherriff’s career path was set. He asked for a sabbatical from his employer, Sun Insurance, to focus on this new direction. America beckoned, and by 1932 he was contracted to Universal Pictures, having and left England for sunny California. He became a member of the Hollywood Cricket Club, a hub of British sportsmen/artists in California. Sherriff also used the money from his success to buy Rosebriars, a five bedroom home in Surrey where he lived contentedly with Constance, his mother.

Academy Award Winner

He wrote several successful screenplays before the outbreak of the Second World War, including ‘The Invisible Man’ (1933), and the ‘Four Feathers’ (1939), culminating in an Academy Award nomination for his adaptation of the screenplay, ‘Goodbye Mr Chips’ (1939).

After World War Two, Sherriff’s screenwriting career continued to blossom. Most notable of his hits includes the iconic film, Dam Busters (1955). In total, Sherriff wrote 21 plays, 1 musical, 10 books and over 30 movies.

Sherriff never married, but his mother was his lifelong companion until she died in 1965. RC Sherriff died ten years later in 1975. By any standards, he led a long and extraordinary life, one that we’re honoured to remember as a former colleague of RSA.